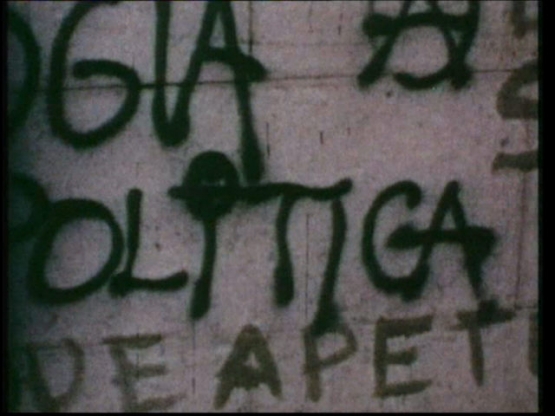

The relationship between art and politics is a long-established one, whether as a form of legitimisation or as a counterweight. This relationship has proven particularly fruitful throughout the 20th century, from totalitarian propaganda to subversive and breakaway movements such as dadaism, surrealism or Fluxus, aesthetic trends aimed at political change such as neo-realism, or artistic expression associated with the defence of civil and women’s rights in the 1970s, and even the reaction to sexual discrimination, exacerbated by the emergence of AIDS in the 1980s, to name a few examples.

Paradoxically, these movements, which intended to break away from the system, were appropriated by the art market, whose speculative valuation was encouraged by a number of middlemen armed with aggressive strategies, and that has dominated artistic production right up until the present day.

The emergence of new typologies associated with mass forms of communication such as photography, video, cinema, television and the internet have been key to the construction of different artistic languages, destroying the aura surrounding artworks, which once distanced them from viewer, as foreseen by the philosopher Walter Benjamin. Museums have ceased to be spaces for the mere contemplation and historical legitimisation of works of art, but have instead become active platforms for cultural intervention. As public democracy has superseded cultural elitism, the viewer has taken on a more proactive role.

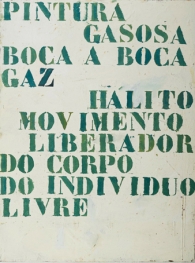

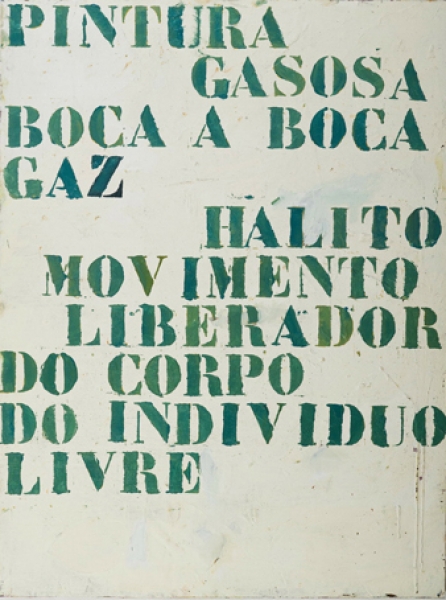

In the aftermath of the Carnation Revolution in Portugal, the critic Ernesto de Sousa, who commissioned the groundbreaking exhibition Alternativa Zero (1977), decried the Portuguese unwillingness to deal with the contemporary, emphasising the need to “call for a new concept whereby art means participating in what is real, in our everyday lives”, while the historian José-Augusto França declared, in response to the same exhibition, that “art is always political”.

The first decade of the 21st century witnessed a further intensification of the relationship between art and politics, reflecting both old and new problems such as post-colonialism, gender and identity issues, injustice and social breakdown, financial speculation and the destruction of the landscape, among others.

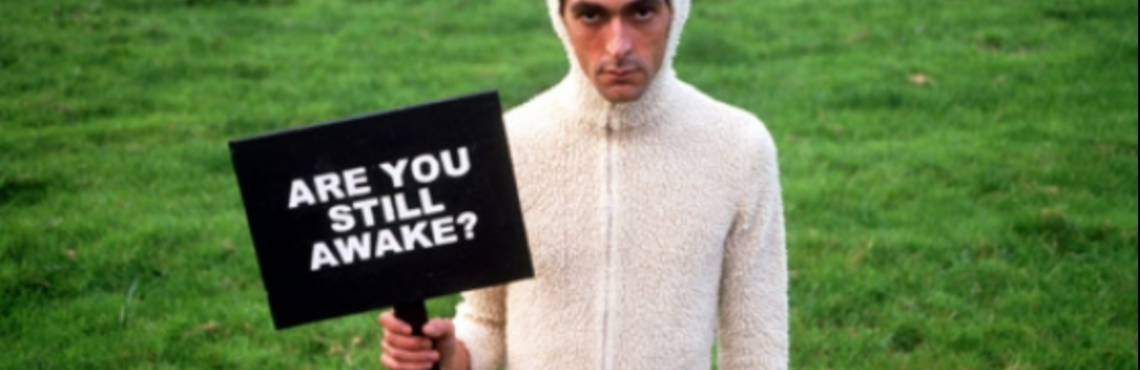

These are the themes covered in this temporary exhibition, which comprises a creative yet citizenship-oriented offering aimed at acting on reality and transforming it through provocation, irony, humour, transgression, protest and violence.

Some gaps in the collection have been filled by the addition of very recent works which were lent to the museum, reflecting the MNAC’s constant and up-to-date dialogue with artists, monitoring contemporary artistic output in Portugal and bringing it to the public’s attention.

Emília Tavares

Curator