The National Museum of Contemporary Art - Museu do Chiado National celebrated in 2007 the fiftieth hundredth anniversary of the birth of Columbano Bordalo Pinheiro, with an exhibition that presents to the public a selection of his works made between 1874 and 1900. There are around 70 works, paintings and drawings, the vast majority belonging to the collection of the museum, but also to other public and private collections. In the exhibition the works are organized into eight nuclei, "Training", "The Radical Painter of petit-bourgeois life", "In Paris, capital of the 19th century", "Modern Painting", "An inventory of the spirits," "With the elapsing of time" "History Painting and and Camonian imaginery" and "Drawing in order to paint" in order to highlight the different moments of his artistic work over these three decades.

With this exhibition, accompanied by the publication of a catalog, the museum paid tribute to an inescapable figure in the history of Portuguese art, author of works such as The Grupo do Leão (1885), Concerto de Amadores (1882) and Retrato de Antero de Quental ( 1889), professor at the School of Fine Arts and director of the museum between 1914 and 1929. The second part of his artistic production, held between 1900 and 1929, the year of his death, will be treated in an exhibition scheduled for 2010, as part of the centenary celebrations of the Republic.

This exhibition presents Columbano Bordalo Pinheiro’s most significant work from the 19th century. His work traces a unique and quite possibly most profound course through the early stages of modern art in Portugal. Columbano was from the very start a natural artist superior to any other, interested in developing a technique that was informed by the issues of his age. Through him, we are able to understand how knowledge of the modern developments of the time in Portugal was attained, its possibilities and interest, the singular results that he achieved, the hesitations and rejections, as well as the cultural circumstances of the intelligentsia whose portrait he extensively painted.

Following in the footsteps of the realism of Eça de Queiroz’s prose and Cesário Verde’s poetry, he adopted naturalism as a means of approaching reality that revolutionised the academic canons of painting. Initially, he painted scenes from bourgeois life that were deeply ironic, but it was in the portrait that his work reached its fullest expression. He developed a distinct technique for constructing figures by using thick patches of paint and an indefinite outline that at times distanced him from a more obvious naturalism and revealed the primacy of the painting and its physical conditions. The critics almost never understood him; indeed, they were never prepared to. In that sense, his modernity was absolute, but in creating his style of painting Columbano still managed to evoke the classical memory of the Dutch and Spanish 17th centuries. As he progressed, the end of the 19th century saw him develop a style that fused modernity with classical influences through the continuous production of portraits for which he invited an entire intellectual generation to sit, and which configured itself as a constellation of signs on the horizon of pessimism that suffused the national cultural scene at the time. It was also at the end of the century that he achieved full and unanimous recognition from the art critics, becoming the official painter for the following century, a century which, however, would not be his.

Pedro Lapa Director of the Museu do Chiado – MNAC and curator of the exhibition

TRAINING

Columbano’s early works were produced at home under the careful instruction of his father, the painter Manuel Maria Bordalo Pinheiro (1815-1880). He graduated from the painting course at the Academia de Belas Artes in Lisbon in 1876 with low grades due to poor attendance and lack of application. He was a student of some of the most important artists of the Romantic generation, such as Tomás da Anunciação, Miguel Lupi, Vítor Bastos and Simões de Almeida, but his apprenticeship was essentially served at home with his father, who cultivated small format paintings of everyday life in the seventeenth century Dutch style. It was this style that he conveyed to his son during lessons at family gatherings in the evenings. Columbano first showed at the Salão da Sociedade Promotora das Belas Artes in 1874 with several at times anecdotal paintings of popular scenes. In 1879, he applied for a scholarship to study landscape painting in Paris, but was passed over by the jury. He applied again in 1880, this time to study history painting, but again to no avail. (PL)

THE RADICAL PAINTER OF PETIT BOURGEOIS LIFE

The year 1880 marked a profound and radical shift in the direction of Columbano’s painting. The works that he showed at the Salão da Promotora and, later, at an exhibition held with his friend António Ramalho were predominantly genre paintings and revealed a particular attention to episodes from Romantic and urban life. Columbano harked back to a realist style of social observation, revealed in the well-chosen but depoliticised peculiarities of petit bourgeois life. He reworked realism with gentle irony and a subtle criticism of manners, possibly as a result of the genre painting and portraits that then defined his new work. Urban life and its respective scenes became susceptible to a body of work that he continued to develop as if in response to Ramalho Ortigão’s invective: “What we need is a painter of manners and an interpreter of human reality."

Columbano’s chronicling of modern life was served by a supremely modern style of painting in which, on the one hand, the descriptive traits of the faces are circumscribed by little signs that define the codes of the actions portrayed and, on the other, the pictorial surfaces take on rhythms and configurations that disconnect the patches of colour from any descriptive function and contribute to flattening and abstractifying the space. The radical freedom of these paintings even made Ramalho Ortigão recoil, representing as they did an unparalleled moment in the affirmation of modernity in Portugal. (PL)

IN PARIS, CAPITAL OF THE 19TH CENTURY

Although he had been turned down for a scholarship in Paris, Columbano used his connections, and King Ferdinand of Saxe-Coburgo-Gotha, through the Countess of Edla, offered him a grant which extended to paying for the artist’s sister to accompany him. In principle, he was to attend the studio of Carolus-Duran, who had admired his work in Lisbon, but in the end that did not materialise. However, from that studio he gained the friendship and admiration of the American painter John Singer Sargent (1856-1925), who tried in vain to get him into to the Academy of Fine Arts. Unfortunately, Columbano made little attempt to get to know young artists and where one would have expected him to immerse himself in the capital of modern art, he complained that Paris smelled of rice powder and oil! By the time his stay reluctantly drew to an end, it was The Louvre above all that had become his main interest. The paintings that he produced in Paris, some ten in number, mark a change in the course of his work: the variations in colour became limited to a range of more fluidly spread ochres, while his backgrounds became darker. The use of light and dark, at times approached with some complexity, made its first appearance in his painting. A dynamic quality and instantaneousness also replaced the traditional pose of the model, as in A luva cinzenta and Retrato do jornalista Mariano Pina, which show a resemblance to a more photographic-style perception. But the finest work from this period was Concerto de amadores, shown at the Paris Salon in 1882. The grand scale contrasts with the intimate motif, while the treatment of the light varies between the suggestion of a classical and modern approach. In final analysis, Columbano attempted to reconfigure elements from the history of painting with a vision that was both modern and simultaneously individual. (PL)

MODERN PAINTING

Columbano’s return from Paris was anxiously awaited, as he was considered by certain critics in Portugal to be the most radical of the modern painters. Meanwhile, the naturalists, grouped around Silva Porto, who introduced the novelty of plein air painting into Portugal in 1880, formed the ‘Grupo do Leão’, named after the restaurant and beer cellar where they used to meet in bohemian revelry. In 1881, they initiated the Pintura Moderna (Modern Painting) exhibitions. Columbano participated from the second exhibition onwards, sending some of his older paintings, and saving his newer ones for the group’s third exhibition, which opened in late 1883, after he had returned from Paris. His work now displayed a new colour palette, the dark backgrounds and use of light and dark from his Paris period making way for light backgrounds on which the darker figures are depicted. There is no attempt to create volume, only flat surfaces, at times with an accentuated thickness of paint, out of which the figures are constructed. Everything is synthetic and reduced to the relationship of the surface treatment, which is purely pictorial, with the perception of the subject and its context. Oddly, Columbano readopted a more modern approach to his painting in which the influence of Manet (1832-1883) was evident. The Portuguese critics, even Ramalho Ortigão who had defended him, now accused him of producing work that was incomplete. Only Mariano Pina, a regular visitor to the Paris Salon, supported him, demonstrating just how out of touch artistically the country and its cultural agents had become. (PL)

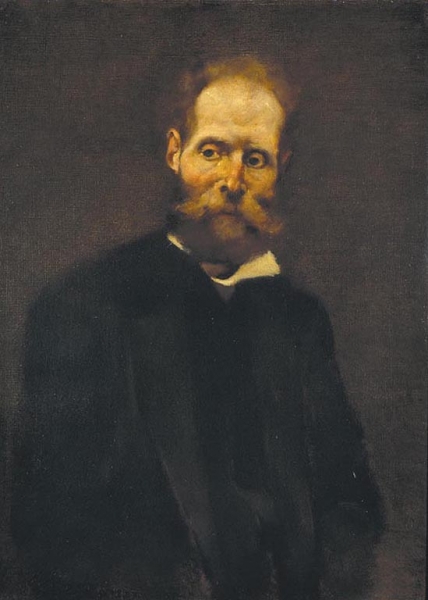

AN INVENTORY OF THE SPIRITS

At the end of the 1880s, Columbano’s paintings underwent a sea change after a visit to Madrid, where he admired Velázquez and the tenebrists, and Paris, then dominated by the Symbolists. The Retrato de Antero de Quental is the first and most significant work from this new period. The dark backgrounds make a return and the subjects appear to emerge from the depths of the darkness. The thickness of the paint is more diluted than ever and gives his subjects a ghost-like quality, so that a vague unreality superimposes itself on the naturalist perception. Eça de Queiroz, reflecting on the style of the last decade of the century, referred to the existence at the time of a tendency to “discredit naturalism” and to create portraits in order to “detach man as far as possible from his own flesh, and eternalise nothing more in him than a semblance of the spirit”. Columbano experimented in the early 1890s with a Symbolist approach by means of a series of portraits of the intelligentsia of a Portugal which at the time was experiencing the bankruptcy of the political and cultural system and of the positivist ideals with which it proposed to change it. Each subject therefore represents the vestige of a work which is absent but which is made present by him, defining as a whole a broad portrait of thought and its circumstances at the end of the nineteenth century. (PL)

WITH THE ELAPSING OF TIME

Alongside this series of Symbolist-style portraits of the Portuguese intelligentsia, Columbano developed other collections of portraits in which an immanent perception crosses naturalism with other heterogeneous references. As a counterpoint to the political and cultural drama being played out, these paintings have a fascination for their reiteration of the traditional understanding of the painter and his ancestral subject matter. On the one hand, he was interested in the elegant and mundane portrait with its modern references, which had its exponents at the time in J. S. Sargent and Giovanni Boldini, and he experimented with it on the high society figures of the era; on the other hand, the traditions of the seventeenth century Spanish bodegónes and the shadowy and calm interiors of the Dutch petit-maîtres, which had always caught his attention, were the sign of a split during this period: the dominant bourgeois taste, dominated by the mastery of the painter. It is, then, the tastes of an era and its protagonists that Columbano’s paintings examine at the threshold of a new century. (PL)

HISTORY PAINTING AND CAMONIAN IMAGERY

As profound and important changes took place in late-19th century Europe, Portugal, on the brink of the modern age, suffered a major economic, social and political crisis. An atmosphere of discontent took hold, caused by the British Ultimatum (1890), a “moment of humiliation and anxiety” (Antero de Quental) captured by Guerra Junqueiro’s Finis Patriae, set against a background of disillusionment. The Camões theme, in its recalling of a glorious past, invoked a crucial unreality, based on the idea of an imperial nationalism forged on the poetic sensibility of the epic The Lusiads and the heroics of its author. This view of history converted the myths and signifiers from national historiography into nostalgic and anecdotal illustrations of moments from the past by trivializing the epic and bringing it into the present.

Columbano’s history painting, staged on contemporary “screens”, revealed a contextual involvement, though more imagined than rigorous, with models of real life, and linked late-century cultural attitudes to the illusion of history-making. A simplifying temporal dimension that deceptively combined moments from a historical past with a need to update them in the present. Readily understood by popular culture in the now established pattern of using themes accessible to the masses, eager for accounts of national glory, history painting dramatized the scenographic depiction of real figures in objective and casual portraits. The success of the narrative, which was neither epic, nor glorious, but implied by the interpretation of the historical, grandiose and natural fact, “grandiloquent and current”, was guaranteed. (Maria de Aires Silveira)

DRAWING IN ORDER TO PAINT

In general terms, drawing was not an independent exercise for Columbano. Rather, it reaffirmed Columbano as a painter, as an artist who used drawing almost exclusively as a means for studying composition, the orchestration of light, the characterisation of anatomical details and the individual poses of figures incorporated into larger compositions. While the drawings record the stylistic variations of this period, very often following the pictorial transformations, it is in the change from one genre to another that these differences become evident: from the intimacy of the petit bourgeois interior scenes, that at times impregnate the portraits, to the mundane character that reveals itself in some of his studies of female figures; or from the realism of the portraits, which vary between a naturalist faithfulness and a desire for psychological characterisation, to the dramatic and theatrical sense of the history paintings. Thus, we witness different pictorial approaches that adopt spontaneity of line as the governing element of the composition, or replace it with the structural value of the light, in a treatment based on patches or markings of light and dark, until achieving a linearity that is free and unfettered by the compositional studies for the large history paintings and decorative series, whose complexity explain the abundance of studies, with special focus on the Camões theme in general and the decorative paintings in the Museu Militar in particular. (María Jesús Ávila)